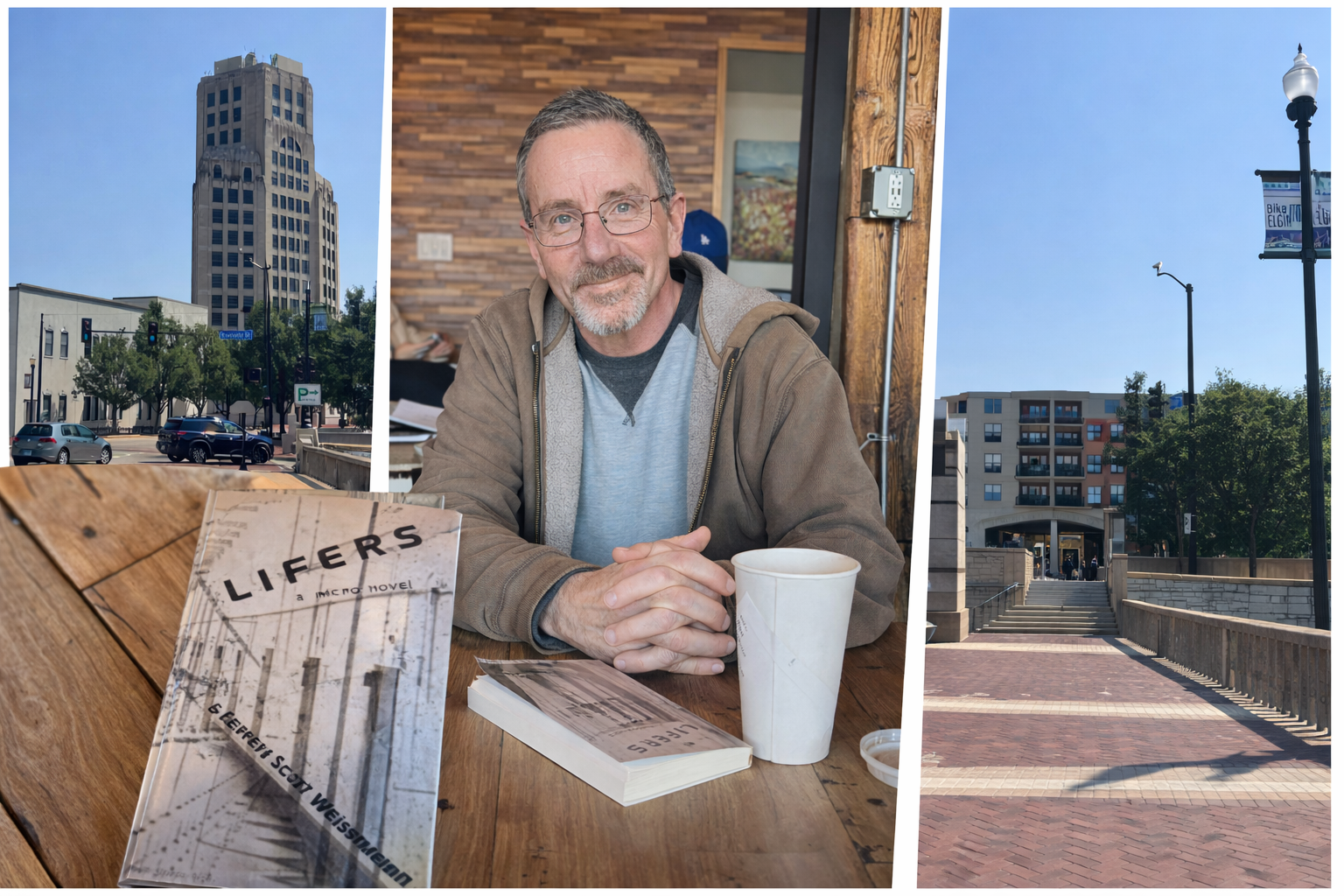

Jeff Weisman has written twenty-seven books. “They are all different,” he says. “But at this point, only two have been published.” That line lands with a kind of calm honesty; because it isn’t a complaint. It’s simply the working reality of someone who keeps writing anyway.

Weisman is a familiar name to Fox Valley Review readers, a frequent contributor whose voice has long been part of the magazine’s intellectual and creative texture. For more than twenty-five years, he has taught English at Elgin Community College, where his impact has extended beyond instruction into the wider civic and cultural atmosphere of Elgin itself, where ideas circulate, where questions matter, and where language still has a public life.

Before that long season of teaching, he traveled across Europe after completing his graduate studies, spending time in places including Prague and Scotland. But travel, in his telling, is less a list of stops than a widening of inner terrain, another way of encountering the world, gathering questions, and testing what a mind does when it’s pushed beyond the familiar.

The Routine: Make Sense of the World

Asked about his creative process and discipline, Weisman is direct: he writes “for several hours every day.” The work begins not with a neat outline, but with something unsettled.

“I start with a question or a feeling or something that is troubling me and try to find a way to bring that notion to life,” he explains. Writing, for him, is not a performance of certainty. It’s a method of inquiry.

He’s also disciplined in what he takes in. “I read a book or so a week,” he says, “and I am constantly trying to expose myself to new ideas or thoughts.” The reading isn’t separate from the writing; it’s part of the same motion: exposure, pressure, discovery.

“For me,” he adds, “I make sense of my world through writing, so I am really driven by that need.”

And when he speaks about endings, you can hear how he thinks about art itself; not as closure, but as ignition. “I am a firm believer that the strongest endings to a work are really a beginning,” he says. “So, I don't try to answer things but raise further questions.”

“I don’t try to answer things but raise further questions.”

Lifers: Prison as Metaphor, Reflection as Plot

His latest work, a micro novel titled Lifers, carries that philosophy into its subject and form. The book, he says, is “about the reflections and insights of a man who is in prison for murder.” The protagonist does not deny the act. “He fully admits his guilt,” Weisman says, “but he doesn't know why exactly his life turned out the way it did.”

The core of the novel is not an attempt to exonerate, but a confrontation with the deeper puzzle of a life. Was he “predestined to be who he is?” Is “some power driving things?” Or is it “his own human nature determining his life”?

And then Weisman offers a sentence that frames the entire work without reducing it: the novel “uses prison to create a metaphor of being trapped in our own selves.”

“Prison becomes a metaphor of being trapped in our own selves.”

How to Read It: Let the Voice Lead

When asked what guideposts he would offer readers, Weisman doesn’t hand out instructions as much as orientation; how to enter the work without forcing it to behave like something else.

“I am a firm believer in the idea that a work of fiction can take its form [in] the development of the work itself,” he says. Readers, in his view, should be open to the way the book builds its own structure as it moves.

“I think readers need to be open to letting the voice and the protagonist's thoughts steer their reading.”

Then he adds the key: rather than imagining plot only as forward motion, he suggests readers consider a different direction entirely.

“Ultimately, in my opinion, rather than thinking of plot as something that needs to develop forward through time,” he says, “I think it might be helpful to consider the notion that plot can also develop inward towards someone.”

That’s not just advice for Lifers. It’s a philosophy of fiction and a quietly radical one.

“Plot can also develop inward towards someone.”

What He Hopes Readers Take Away

Without spoiling anything, Weisman says he hopes readers take away two things: “an enjoyment of an interesting and original work of fiction,” and “a deeper appreciation of their own life.”

There’s no grand claim in it. No sermon. Just the belief that good fiction sharpens perception, and that noticing your own life more clearly can be one of the most meaningful outcomes a book can offer.

Making Time, Not Finding It

Balancing writing with everything else, Weisman doesn’t romanticize the struggle. He refuses the premise that time is something you stumble upon.

“I do not believe we find time,” he says. “I think that is foolish. We make time.”

As a writer, he makes time “early in the morning” to work on his craft. The logic is practical and uncompromising: “The only way to get something done is to do it. So, I stay focused on doing it.”

Working early, he says, “allows me to have time for the rest of my life.” Writing isn’t squeezed into the leftovers. It’s scheduled like a serious thing; because it is.

“We don’t find time. We make time.”

The Public Intellectual: The Artist’s Role

Asked what he considers most important about his work as a public intellectual, Weisman speaks in terms of role and responsibility. “I truly believe in the role of the artist in our society,” he says.

And he’s clear about the stakes as he sees them: “Today, we are dealing with a stifling of voice and a suppression of ideas and thinking in our society.” He would like to believe his work challenges that.

At the same time, he doesn’t pretend to stand above the struggle he describes. His questioning isn’t a posture; it’s personal. “Additionally,” he says, “I do believe I am raising questions that need to be explored, if for no other reason than I am struggling with them myself.”

Advice to Writers: Get to It

For aspiring writers and public intellectuals, his advice starts with urgency and ends with joy.

“Get to it,” he says. “Read. Read. Read.”

Then: “Follow your own interests, pursue your own path.” And a warning that feels like hard-earned clarity: “If you are trying to make someone happy, in most cases, you are not trying to make yourself happy.”

Writing is not easy. “Writing is tough,” he admits. “But have fun.”

And he closes with something that feels both intellectual and deeply human: “Nothing is more intellectually challenging than developing something completely new to you. The surprise of your own direction is worth it.”

“The surprise of your own direction is worth it.”